Today, we’re publishing three — count ’em, three! — interviews here at Jolly Olde Terribleminds. On first pass, I don’t like to crowd up with interviews, and I thought, mmm, maybe I’ll spread these out. But here’s the thing: these interviews talk to three writers who each share a kind of intellectual space. All three are cracking short story writers, all three come out of crime writing, all three have killer novels (two of them published, one on submission), and to boot, all three know each other. So, my thought is, let’s let these interviews feed into one another. Right? Right.

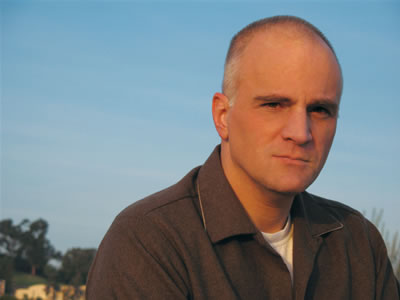

First up? My alpha clone, Dan O’Shea. Dan’s a grizzled bad-ass of a writer, but incredibly thoughtful and smart about how and what he writes. His prose astonishes me. This week he’s got his first collection of short stories out — some of which originated here at terribleminds — and you need to check it the fuck out. It’s called OLD SCHOOL and, I’ll be honest, I wrote the foreword. You can find Dan’s website here — danielboshea.wordpress.com— and track him down on Twitter (@dboshea).

When you’re done here, check out the other two interviews:

Chris Holm

Hilary Davidson

This is a blog about writing and storytelling. So, tell us a story. As short or long as you care to make it. As true or false as you see it.

It’s July in the Summer of Fishing, or that’s how you remember it. The summer you bought that Diawa spinning reel over at Zayre, the summer you got over being afraid of the old black guys that would sit along the bank of Blackberry Creek by the old railroad trestle on the bike trail, drinking whatever it was they drank out of the bottle wrapped in the paper bag, the way they’d talk to each other, trading insults that would have been fighting words in your world, but they’d just laugh about them, at least the insults you understood. The guys that shook their heads at the rubber worms you’d tried to use. The guys that showed you how to catch carp and catfish with wadded up balls of Wonder Bread dipped in some foul smelling crap that they kept in a rusty Folger’s can.

It’s a month or so before you bought the fly fishing rod, before you and Brian tried practice casting with it in the gloaming after dinner and found out you could fly fish for bats. Almost a decade before Brian was the best man at your wedding. Of course, Brian’s dead now, and even that’s five years back.

The summer you found that lake.

You called it a lake, and I guess it was near enough to one in your experience, this part of Illinois not being much stocked with them. Fifteen acres maybe, all in. A pond really, and not a naturally occurring one. You know that now. An irregular pit bulldozed into some old wetlands, developers trying to contain the runoff, keep the water out of the subdivision up the small slope on the east end, back when Orchard Road wasn’t Orchard Road yet, just a nameless gravel track. Now, it’s four lanes. Now, the golf course would be across the street. Now, you’d be able to see Home Depot from here. Now, you’re 52. Then, you were 13.

Your mom made you bring your brother with you, Patrick. He would have been what? Four? Maybe five? Ruined the spirit of the thing. Because that summer, in spirit you were one man alone on the edge of wilderness, pitted against nature, trying to coax beasts from the deep. But if your mom sent Patrick along, then this wasn’t any wilderness, no danger lurked near. If they let you bring Patrick, you were still just a kid fishing in some neighborhood pond. She dropped you off on the paved road at the edge of the subdivision, east of the pond.

You tried not to look east, because west it was still woods, still marsh, still wilderness. Wilderness to you, though it was really just saplings and scrub reclaiming an abandoned farm field, a field some developer had already bought, one they just hadn’t torn up yet. Wilderness if you ignored the hum of tires to your left, probably a couple hundred cars an hour driving up and down Galena.

But these tires weren’t on Galena. These tires were crunching along the gravel across the pond. An Impala, an old one, mid-sixties, the red paint faded to the color of diluted blood, the wheel wells and quarter panels lipsticked with rust. The car stopped where the pond pinched in, where it narrowed to a wasp’s waist of mud and shallow water, maybe ten yards across, where you could wade from one side to the other without getting your ankles wet. Two guys in front, you could see that. They just sat there a minute, didn’t seem to be looking at you, just sat there.

You knew you should leave. You knew you should take Patrick, walk up that embankment to the paved roads and the houses. You knew it and you cast your line back out into the pond anyway.

The passenger door opened and a guy got out. Twenty maybe, twenty five. Blue jeans, a ratty t-shirt, stringy blond hair to his shoulders, a Winston bobbing in his lips. He was carrying a crutch, but he wasn’t using it. He smiled at you.

“You boys catching anything?”

You shook your head. “Not today.”

He nodded. “Too hot probably.”

“Probably.”

Then he’s sloshing across that narrow gap. Then he’s standing next to you. Patrick’s on the other side of him. The guy just stands there.

“What you using for bait?”

You reel in, hold up the tip of the rod, show him the little plastic minnow with the small treble hook behind the flashing Mepps spinner.

He snorts. “Shit kid, I doubt there’s anything in this ditch big enough to get its lips around that.” And you know he’s not going to help, not going to tell you about bread balls and stink bait. You know something bad is going to happen, but you keep trying to act like it isn’t. You cast out into the pond again.

He finishes the cigarette, flicks the butt out into the water. It hisses, a sunfish rises and pecks at it, spinning it a little.

“You got any money?” he says.

And you don’t. Not a cent.

“No.”

He touches your ass, running his hand across the back of your pants. Your insides freeze. But he’s just feeling your pockets for a wallet.

“Left you wallet home, huh?”

You just nod, knowing if you speak right now, your voice is going to crack. You don’t want your voice to crack.

The guy bends down, opens your tackle box, dumps it out in the dirt, paws through it, takes a quarter he finds glinting in a gray pile of spilled splitshot.

“Waste of fucking time,” he says and takes the first step back toward the car.

“I’ve got money,” Patrick says. Little kid’s voice, petulant, defiant. “But you can’t have it.” Turns out Patrick has a nickel in his pocket.

The guy stops, steps toward your brother, and all the embarrassment and rage and confusion short circuits you a minute and you whip the rod around, smacking it against the guy, the hook catching in his shirt, tearing it open as it rips away.

And the guy turns, the crutch he was carrying already in motion, him holding it down near the footpad, swinging it like an ax.

You shuffle just enough that it only glances of your head, slamming down onto your shoulder, the screw and the wing nut out sticking out in the middle where the handhold is bolted in bite into your flesh, gouge out a wound, and you backpedal into the water, trying to get some distance as the guy swings the crutch again, like a bat this time, in from the side.

You bunch your shoulder up, taking the first part of the blow on the meat, but the crutch skips up, hits you over the ear, and there’s that moment where time stops, where the force and the feel and the sound of the blow translate into this flash of light inside your head, where any outside sight or sound is cancelled out so that when your sight comes back, it’s skipped a frame, like a projector where the sprocket slipped, and you see that he’s already in mid-swing again, a three-quarter angle this time, from the top and side, and you turn your back, bending, and he blow lands across your scapula, that wing nut biting in again, and you hear a crack and you think for a moment that your bone is broken, but then you hear a splash and most of the crutch is bobbing in the middle of the pond in a riot of fresh ripples, and you turn and the guy is holding maybe six inches of busted wood now, and you’re screaming at Patrick to get into the water, to get behind you and Patrick is saying he’ll get his shoes wet and you scream “Get in the water, goddamn it,” you’re thinking maybe the guy won’t want to come in after you, won’t want to get wet, and even that idea feels stupid, but that light strobing inside your head and it’s the best you’ve got, and your brother gets it finally, the threat, the danger, gets it at the same time the guy does, the guy reaching for Patrick, Patrick running around him, and he splashes into the water, crying now, and you put your left arm back, holding him behind you, and you remember the filleting knife on your hip, hanging from your belt in its leather sheath, and you remember how sharp that is and you pull that, backing into the pond, the water over your knees now, almost to Patrick’s shoulders, so you stop, holding the knife out in front of you, not sure how far this is going, but knowing that, if the guy comes in after you, you have to start slashing.

But he doesn’t. He kicks your tackle box into the pond, throws your pole in after it. Stands there looking at you a minute, pulls the pack of Winston’s out of the pocket of the t-shirt that hangs on him ripped open, digs a lighter out of his jeans, blows a long stream of smoke out into the air.

“Fucking kids.”

He splashes back across the wasp’s waist to the Impala, and the car spins off in a rooster tail of dust and gravel, heading south back to Galena.

Later, at home, your back and shoulder bandaged, your scapula striped with bruise, the police come and gone, you hear that this Chris kid, a guy that had been two years ahead of you in school, big guy, star of every team, the date of every cheerleader, that guy had gone down to Starved Rock State Park that same day. He was fucking around with some friends and had fallen off a cliff. He was dead.

And you realize this. It is all wilderness.

OK, Chuck, you said a story. You said as true or false as I see it. That story is mostly one, some of the other. But, as I read back through it, I find myself absently rubbing the scar on my left shoulder.

Why do you tell stories?

Maybe the only useful thing I learned from religion classes through thirteen years of Catholic schools, if you count kindergarten, is the power of parables. People listen to stories. You can convey a message through stories with a power that a lecture will never equal.

That, and the truth is boring.

Give the audience one piece of writing or storytelling advice:

Always read your stuff out loud.

Writing is just a system humans dreamed up because the sound of speech was transitory. I have to wonder, if we’d had recording equipment back 5,000 or so years ago when writing first developed, if we even would have invented it. Would there still be documents if we already had a way to make speech permanent, or would everything just be on tape? Language was oral first, writing is just a way to make speech permanent.

When you read something out loud, you catch things with your ears that you don’t with your eyes. All the awkward little constructions that your eyes rolled right over, the word you are repeating too often, the dialog that’s glaringly bad when read out loud – your ears will catch bullshit that your eyes never will.

Maybe it’s the frustrated actor in me, I don’t know, but I really love to read my stuff. Here, try some. Here’s a reading of Shackleton’s Hootch from my collection, Old School. It’s appropriate that I run this one, because it was something I wrote in response to one of Chuck’s occasional flash fiction challenges.

I really do like the whole audio thing – in fact, anybody that buys OLD SCHOOL will find an offer in there to get a free audio book version. Just a little something I’m trying to differentiate my offering from the burgeoning pile of e-books out there.

What’s great about being a writer, and conversely, what sucks about it?

That moment when you are in perfect communion with a character, when you are channeling a person of your own creation as if you have tapped into an external psyche, when you completely understand a person you could never, yourself, be, and that person’s world, their words, their being, all of that is spilling out through your fingers as if that character had opened a vein and you were writing with their own blood, that’s a hard feeling to top.

The business side of it, all of that sucks. This whole do I self-publish thing, all the Amazon crap, all the possible distribution channels and alternative ways to market – you could make a full-time job out of understanding that whole mess, and none of that appeals to me in the least. It makes a little cloud of despair in my head when I think about it, so I try not to.

Favorite word? And then, the follow up: Favorite curse word?

Impossible question. You’ve only got one kid right now, so you don’t get it. Somebody asks you who your favorite kid is, that’s easy for you. I’ve got three. But we’re writers. Words are our children, too.

Comes to words, there isn’t even an exact answer to how many there are in the English language – 200,000 or thereabouts. I’ve read that the average person knows between 12,000 and 20,000 of them. I’d like to think that most writers know more. But a favorite? I can’t say I have one.

There are those moments though, as a reader and a writer, where you find the perfect word in the perfect place, usually one used a little off-center, one that jolts the reader into a new mindset. Hell, in the story I just sent you today, I said the rust on the old car was “lipsticked” around the wheel wells. I kinda like that. I think the reader will get that, but will get it in a more exact way than if I’d just said an old, rusty Impala. So maybe this morning lipsticked is my favorite word. And it isn’t even a real word.

As to curse words, when I was in high school, my sophomore football coach was a nutjob guy who was raised in Brazil. He was also the Spanish teacher. There was some foreign phrase he used to scream at us in practice when he got pissed, maybe it was in Portuguese, maybe it was in Spanish, maybe it was some Creole of both, I don’t know. But he wouldn’t tell us what it meant. Years later, I saw the guy and asked him. He smiled, and told me when he got mad at us he would scream “You have the prick of a fish.” That’s pretty good. Curse words alone aren’t all that special. It’s the constructions they’re used in that make them pop.

Favorite alcoholic beverage? (If cocktail: provide recipe. If you don’t drink alcohol, fine, fine, a non-alcoholic beverage will do.)

I’m a Manhattan guy. I’ll drink a lot of stuff, although not gin, never have liked gin, and I’m kind of meh on vodka, too. In fact, when it comes to rum, I’ll take dark over light every time, so I guess I’m not big on clear liquors. Beer, sure, but something with body and taste – I think the Sam Adams people put out a fine line of products, and I especially like a lot of their seasonal offerings. Wine, yep. Red more than white. In the summer, there’s nothing like whipping up a nice batch of sangria – I’ve got a couple of favorite recipes for both red and white versions – and, if it’s a hot week, there’s probably a pitcher of one of them in my fridge. Sangria, by the way, isn’t just wine with fruit juice in it. There’s brandy, or maybe peach schnapps, maybe some triple sec – there’s something in it to give it a backbone.

But if I’m going with one drink, it’s the Manhattan. It was my father’s drink, I write at my father’s desk. At the moment, I’m sitting in my father’s chair. Filial loyalty. Two measures of bourbon (rye if you have it), one of sweet vermouth, a splash of bitters (or a couple in my case), gotta have a cherry, and a little splash of the cherry juice from the bottle doesn’t hurt, either. On the rocks in a rocks glass. If I go to a bar and they bring my Manhattan in a martini glass without ice, then I know the place is just too precious for me. So a Manhattan. It’s simple, it packs a punch and it makes me think of my dad.

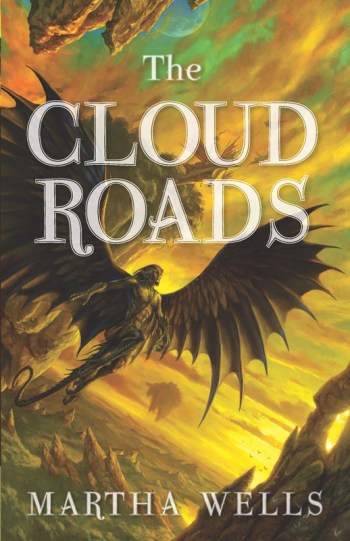

Recommend a book, comic book, film, or game: something with great story. Go!

I’m going to go old school on you. The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene. He’s a guy too often overlooked in my book. Pick that up. Hell, anything by him. Saul Bellow’s another one, a guy who seemed to have a much larger public literary reputation when I was younger, but who now has drifted into that obscurity of only being read in lit classes.

Funny thing, I guess, because you said great story, and when I think back on the books by either of these two, story isn’t the first word that comes to mind. Character does. Atmosphere does. Mood does. Gestalt does. Of course, all of that has to be wrapped around a story of some kind, but story alone isn’t enough.

Story matters more in genre fiction, I think. If I had to pick someone in the crime genre that consistently cooks up a great story, but still bakes in the good stuff, I might go with John Sandford.

What skills do you bring to help the humans win the inevitable zombie war?

Well, if the walkers have already eaten John Hornor Jacobs, I’ll be the guy who still knows about his zombie herding idea. Not going to give it away here, spoil his This Dark Earth launch, but it is the key to final victory.

You’ve committed crimes against humanity. They caught you. You get one last meal.

I’ve always found the last meal thing kind of paradoxical. From the executioner perspective, you’re going to kill the guy because he’s so horrible, so what’s with stuffing him with his favorite eats first? From the executionee perspective, how much are you really going to enjoy this meal when the only thing you can taste is the idea of your own death?

Again, hard to say. Probably depend on my mood that day. Don’t have to worry about my heart at that point, I suppose. Maybe a big slab of St. Louis style ribs, maybe a thick porterhouse, medium rare, slathered in minced garlic and sautéed mushrooms. A side of lobster newburg maybe.

What’s next for you as a storyteller? What does the future hold?

How the hell should I know? My short fiction collection, OLD SCHOOL, comes today from Snubnose Press. I’ve got two novels out on submission, and a third one will be joining them real soon. I’m writing a horror/crime thing now.

One of my novels, ROTTEN AT THE HEART, is my Elizabethan first-person Shakespeare as a private dick thing. I’ve got a couple more ideas for ol’ Will if that ever sells or, who knows, maybe even if it doesn’t. But I’ll work on what I’m working on now, and then I’ll worry about tomorrow. Sufficient unto each day is the evil thereof.

OK, maybe I learned two things in religion class.

What’s the art of telling a good short story as opposed to something longer form?

Funny thing is I’d never written a short story until after I wrote a novel. Before I finished the novel, I was just this guy who always wanted to be a writer, and who then was cursed by finding a way to make a living as one. But my living is writing marketing and educational material for professional services firms – primarily accounting firms as it has turned out. So I’ve spent thirty years writing about the tax code and such. If that won’t make you want to write about killing people, nothing will.

I’d mess around with writing a novel now and then, but that never had a deadline attached, and it sure as hell never had a payday promised to it, so that always got shoved to the back burner. I had a family, responsibilities – writing’s just a way to pay the bills, I’d tell myself, and I’d turned it into a pretty good career. This novel stuff? It started feeling like wanting to play third base for the Cubs. It started feeling like one of those childish things you put aside. And I pretty much did.

My best friend since fourth grade, best man in my wedding, he wanted to be a writer, too. Ended up being a cranberry farmer. We used to talk about the books we were going to write, and we’d both mess around with them. Coming up on five years ago, he crashed his car on Halloween night. I got the call the next day. He was dead. And when his family went up to northern Wisconsin to pack up his stuff, they found his manuscript, all typed up, all finished, in the desk drawer.

He was that friend you make once in your life if you are lucky, the one that is with you all the way from being a boy to being a man and beyond. He taught me a lot. Even in that final act, he taught me something. Taught me we only have so much sand in the glass, and none of us knows how much that is. If there’s something you want to do, you’d best commence to doing it. So I commenced to writing a novel. Found out there’s just as much time for things as you make, and there was time enough for that.

But this whole online writing community? I knew nothing about it. Bouchercon, the other cons, the Facebooks, the blogs, the tweeting? Never heard of them. (Hard to believe, I know, given my profligate Twitter habit now.) But I wrote a novel, got an agent in about a month, figured I’d be Steven King by the end of the year. I mean hey, this shit seemed pretty easy. Of course, that was three years ago, and my agent is still shopping that novel today. Shows what I know.

But she told me I should think about a blog, maybe get on twitter, all that stuff. I did. And pretty soon I ran into my first flash fiction challenge.

Blame Patti Abbott, a fine writer in her own right who’s collection, Monkey Justice, is a must read. I’d never heard of flash fiction, but somebody sent me a link to a challenge she was running on her blog – write a story, 1,000 words or less, set in or around a Walmart.

A thousand words, I thought. Impossible. So I had to try it. And the resulting story, Black Friday, reinforced for me one of writing’s most valuable lessons – strip it to the bone. Or, as the Bard once said, “When words are scarce, they are seldom spent in vain.”

I was hooked. Short fiction became a major food group in my writing diet. Not just for the stories themselves, but as a kind of training for when I’m in the middle of a novel. When I’m writing a novel, I have a tendency to meander, to get a little flabby.

Meander, you say? You? Surely not. I mean it only took you what, Five or six paragraphs to even start answering Chuck’s question?

Well, that’s another lesson, maybe. Good storytelling isn’t always a frontal assault. Sometimes one story starts out as another. Sometimes the real story kind of sneaks up on you. Sometimes a story is like a river, just a little trickle at first, flowing this was and that, picking up a tributary here and there until it builds its force. Then, it will carve a canyon through a mountain instead of going around it.

But yeah. I spend a fair amount of time on short fiction these days. A few hours back in the short fiction gym puts an end to the flabby shit. Maybe not to some of the meandering, because, like I said, meandering has its place. But there’s nothing like a short story to remind me that the flabby writing has to go. It reminds me that you can lose a reader any time. With this sentence, or with the next one. Strip it to the bone.

OLD SCHOOL published by a small e-publisher, Snubnose Press: what’s the value of a small publisher over a larger one?

Because Snubnose is the only publisher I’ve had to this point, that’s hard for me to answer. For me, it came down to this. I had a growing collection of short fiction. People seemed to like it. I wanted to pull it together, get it out into the world, see if I could get a broader audience for it.

The big publishers, they don’t put out that much short fiction, especially not from new authors. Frank Bill is the one exception I can think of, and for damn good reason. If you haven’t read Crimes in Southern Indiana yet, stop right now and do so. It’s OK, Chuck and I can wait.

So my choices were pitch it to one of the smaller publishers or self-publish.

I just don’t want to mess with self publishing. I don’t want to design a cover, format a document, be the only set of eyes proofing or editing something. A man’s got to know his limitations.

And I had another concern. Amazon has opened the floodgates on self-publishing, and the vast majority of that flood has been a stinking river of effluvium. Badly written stories, barely edited, rife with errors, often offered for free or near to it. I think readers are beginning to drown in that cesspool and are looking for some beacon that offers hope that a download might be something other than just another half-dissolved turd bobbing in the piss warm stream of sewage that the self-publishing revolution hath wrought.

A publisher’s name attached to a book offers that hope, even if it is a smaller publisher like Snubnose. It means somebody who cares enough about writing to set up a publishing company has vetted the book, given it their blessing, invested their time in it, attached their reputation to the author’s. Even for a small e-house like Snubnose, the titles that make it through are a tiny fraction of those submitted. For the reader, that means the publisher has strained through the distasteful river of crap to pluck out the occasional tasty bits.

You hear a lot of railing against gatekeepers from the self-publishing crowd – how agents and publishers are artificial arbiters standing between the reading public and this damned up reservoir of genius. And there are some heady drinks of genius to be had from that reservoir. But you have to gulp down a disproportionate amount of foul treacle to find them.

How are the stories in OLD SCHOOL emblematic of Dan O’Shea?

The collection is entitled Old School because the characters in these stories all have some miles on them. TV and movies are the predominate forms of storytelling in popular culture, and if you drew your view of the world from those sources, you’d think most everybody was some hard bodied twenty- or thirty-something posing through life’s dramas in a Hugo Boss wardrobe.

I don’t write about those people. The protagonists in my stories tend to be middle aged or older. They’ve suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune and often have not prevailed against them. But they also aren’t the dispossessed loners that dominate a lot of noir fiction.

A popular meme in a lot of crime stories is that old saw that having nothing to lose makes a man dangerous, desperate, a better protagonist. I think that’s bullshit. Having nothing to lose means you’re playing with house money. It means the only ones with anything in the pot are everybody else. Might as well play out that hand, all it has is upside. Having nothing to lose means that all you have ever been is a loser.

No, having something that matters to you, bearing the scars that earning that something cost you, having known life’s successes and its failures, but having shown that you have grit enough, guile enough, to have had some of the former, for me, that makes an interesting character. Show me a man who has worked his whole life for what little he has and now finds that in danger and I’ll show you a desperate human being. A dangerous human being. And I’ll write you a story.

You don’t tend to write happy, fluffy stuff — where’s that darkness come from? How do you temper the grim stuff for readers — or, do you?

The story I started out with, that’s mostly memoir. Some embellishment around the details aside, that happened to me.

Now, as a kid, I lived as charmed a life as this nation offers. Dad was a doctor, and a good one, so we had money, creature comforts, good schools, loving parents, all of that. Dad was the kind of doctor that cared way more about his patients than he did about money. Dad was the doctor who, back in 1965, quit the local country club when the clinic he worked at hired a Jewish doctor and that club wouldn’t let him join – got a lot of the other docs to quit, too. The club changed its policy, but Dad never signed back on. Dad was the doctor that was still making house calls in the 1990s. He was the doctor who kept patients for life, who was treating the grandchildren of the patients he started with by the time he retired. He was the doctor I’d find staring blankly over a cup of coffee at the kitchen table some mornings, still wearing the clothes he’d left in the day before, having been at the hospital all night because one of his patients was dying and, even if there was nothing he could do to stop it, he’d be there for it. At his wake, person after person came up to me to introduce themselves as “one of your dad’s patients.” I tried to think of a doctor I’ve had whose wake I’d bother to go to. I couldn’t.

He was and remains the most decent human being I’ve ever known.

That caring extended to his family. I remember my freshman year in high school, we had a football game in Woodstock, maybe 30 miles from our house, way out in the sticks. Our freshman games were on Monday afternoons, started about 4:00. It was a shitty day, pouring rain, cold. At some point in the fourth quarter, I’m running off the field after we scored, and I see my old man standing there on the sidelines, soaking wet, he’s pants cuffed with mud, clapping for me. He’d knocked off work early, driven out into the boonies, just so he could stand in the rain and catch the last quarter of my game. He was like that.

So I was raised in the best of circumstance, yet that story I started with? That still happened. I still got mugged, I still had to protect my kid brother at knife point, and the very same day this other kid I knew, a kid who was pretty much a god in my eyes, that kid fell off a cliff and died. A few years ago, my best friend died in a car crash. A week ago, in Naperville, next town east from here, a town that’s always making that list of Best Cities to Live In or Best Places to Raise Your Family, there was a fight in a bar. Not a biker bar, not some roadhouse. An upscale joint, the sort of place where one MBA who met another MBA on match.com might pick for a first drink. Some guys got drunk, got into it, and this twenty-two year old kid tried to play peacemaker, got in the middle of it, tried to break it up. Took a knife to the heart, bled out all over the nice oak floor.

One my favorite openings to a book is the beginning of Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon. Somewhere in the first couple paragraphs there is this line: The world has teeth, and it can bite you with them any time it wants.

We’ve all got some teeth marks on us somewhere, but fiction is usually about amplifying the everyday, so in my stories, life has bit down hard and locked its jaws.

I don’t always temper that. Some of the stories are just dark, period. But in many of them, there is a note of redemption. Thin Mints comes to mind. That’s probably the one story of mine that’s gotten the most traction – been published in Crimefactory, showed up in the Noir at the Bar anthology, got nominated for some award last year. In that story, you have an everyday guy who throws away everything – family, job, self-respect – in pursuit of his selfish appetites. But in the end, he’s confronted with a hard choice, finds a line he won’t cross, redeems himself.

ROTTEN AT THE HEART sees Shakespeare-as-shamus: what’s the trick to writing historical fiction? Do the facts ever get in the way of the fiction?

Chuck, you and I have famously disagreed on the role of planning (I say famously because it happened on your blog – what happens on my blog happens in obscurity). You like outlines and character bibles and such, I prefer a more organic process – placing characters I like in situations I find interesting, and then just following them around my head and seeing what they do. Now, having written exactly one piece of historical fiction, I won’t hold myself out as an expert, but here’s what I found. I didn’t need an outline for this one, because history provided it.

The story is set in the summer of 1596. Henry Carey, the First Baron Hundson, the Lord Chamberlain and the sponsor of Shakespeare’s theater troupe, dies. That actually happened. A couple weeks later, Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, dies. That actually happened. I refer to the Rising of the North in 1569 and a Spanish raid on the southern English coast in 1595, those actually happened. Marital tensions that I include between Shakespeare and his wife? They may not be true, but there is substantial speculation of the same nature offered by numerous Shakespearian scholars. A guy named Radcliffe, who was basically the Queen’s designated torturer, plays a key role, as do George Carey, the Second Baron Hundson, some of the Queen’s other ministers and Elizabeth I herself. And those are all real people performing their real offices.

Outside of historical events and people, there are realities of life in Elizabethan London that inform the story – the rise of Puritanism and its antipathy to the theater, the banishing of “entertainments” to districts outside the city proper, the growing power of the Bourse (the birth of what we would now call a stock exchange) and the beginnings of the competition between the power of the crown and the power of private capital.

Taken together, all of that formed a virtual outline for the story, provided a historical skeleton I had only to flesh out. So the facts drove the fiction, they didn’t get in the way of it. In fact, the most improbable part of the book – maybe the most improbable thing I’ve included in any of my books so far – is an event from history. The famed Globe Theater, the venue most associated with the Bard, really was built in a day. Due to a real estate dispute, Shakespeare’s troupe really did disassemble their theater in Shoreditch and, in a single night, transport the boards and timbers to the Globe’s location in Bankside, where it was raised the next day – and without power tools. Had that not actually happened, I would never have dared write it, but it did, so I did – and it plays a central role in the story. Although, historically, that happened a couple years after 1596. I’m no Elizabethan scholar, so I’m sure I’ve made other historical errors, but moving that up a couple of years was the biggest liberty I took knowingly.

I like to say this: Rotten at the Heart didn’t really happen. I don’t think Shakespeare was ever blackmailed into serving as a royal sponsor’s private dick. But it could have happened, because the facts presented in the story and the historical realities that provide the story’s tension and motivations are all, to my knowledge, true.