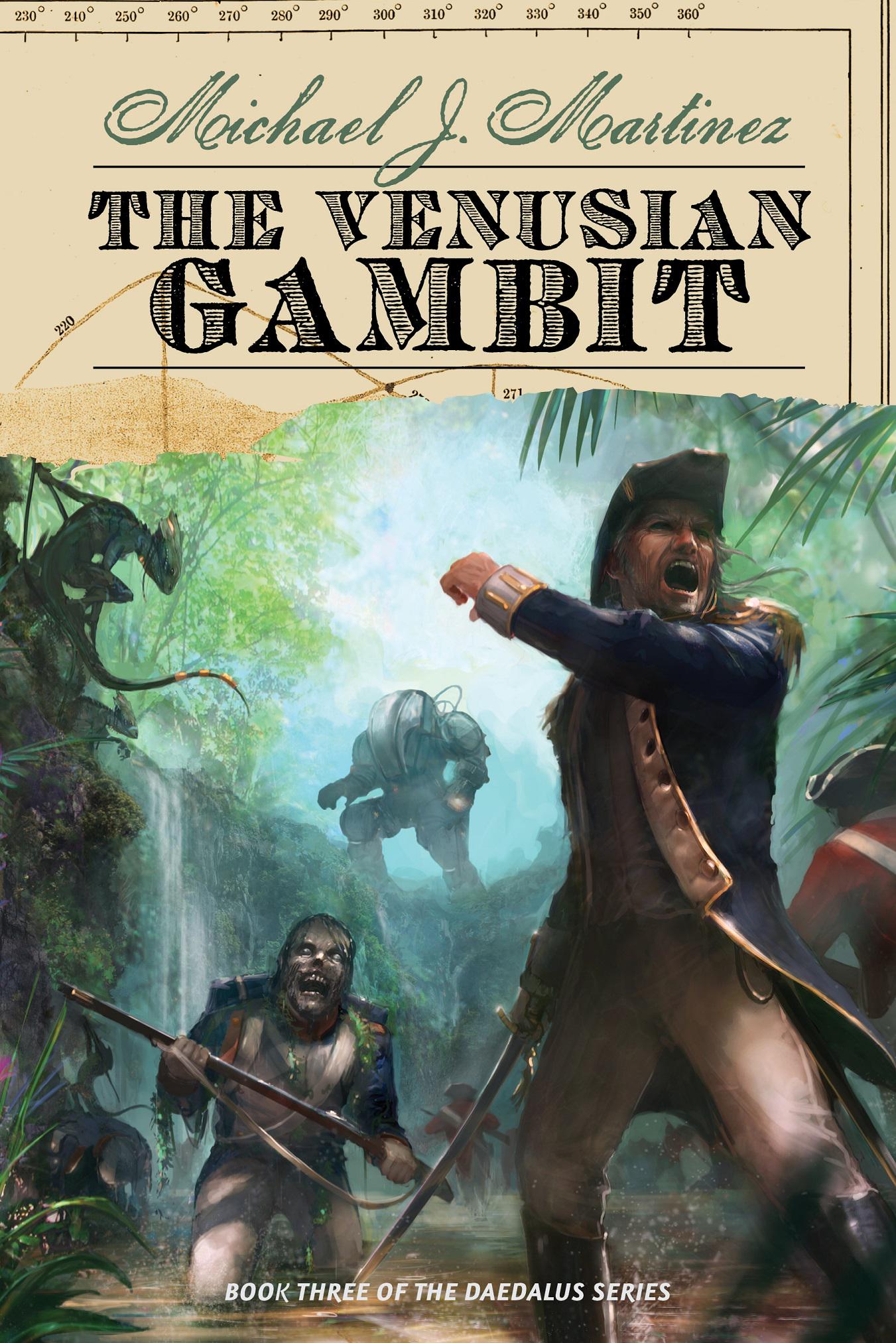

(art above by Kate Leth, who is awesome)

(and below, you will find some spoilers, so you are very much warned)

Over here, you have Max Max: Fury Road, a film that may not have won the box office this weekend, but did a pretty Herculean effort ($45 million) for an R-rated film based on a very fringe franchise with aesthetics that go well against what anybody would think would sell actual tickets.

In the other corner, one of the most popular television shows on at present: Game of Thrones. Pseudo-medieval epic fantasy serialized for pay cable, also very R-rated (well, TV-MA, I guess), and perhaps also a surprise that it connects so well with the popular consciousness.

Both are, in their own way, very similar worlds.

One is post-apocalypse. (Though exactly how or why, we do not know.)

One is pre-apocalypse. (“Winter is Coming,” remember.)

Both are brutal, backward worlds. All too often harsh and unforgiving. The GoT world is probably more advanced than the Mad Max one, in a lot of ways — at least socially. In GoT you’ve got pretty gardens and big cities and varied climates. Mad Max eschews all of that. It’s basically a dust-fucked hell-hole. Occasionally damp, mostly dry and abrasive. Society has dissolved. People are not so much people as they are animals and zealots only. It’s all just sand in your chastity belt.

Both are, you could argue, male-driven worlds. Grotesque, feudal places lorded over by grotesque, wretched men. You’ve got Immortan Joe and the Bullet Farmer. You’ve got Joffrey and Bolton and a gaggle of other spectacular assholes. Both in fact feature comically evil men. Like, so evil it’s just fucking ridiculous. In Mad Max, you might argue it’s less evil and more straight-up lunacy, but you don’t get the feeling these are bad dudes with good sides. They’re just monsters. And guys like Joffrey and Ramsay Bolton are so eeeeevil that the show affords us every chance to watch them plucking wings off of butterflies (metaphorically). Which, admittedly, maybe gets a little old, but what the hell do I know? It certainly works to make you hate them.

If both are male-driven worlds, you can then take a pretty good guess how women are viewed in these worlds? Spoiler warning: it ain’t good. Women ostensibly have a higher position inside Game of Thrones, where they are at least viewed as more than just “things.” In Mad Max, women are objects. They are sources of production, more or less — animals for breeding, for milk, and for all that we can guess, meat. They are post-apoc livestock.

Some folks will say — okay, there are topics and subjects you can’t write about. Which is nonsense, obviously. Everything is the domain of fiction. Nothing is forbidden, everything is permitted. It must be, for fiction to maintain its teeth. Fiction only has meaning when everything is permissable. Rape and sexual assault is one such topic — some will say it’s off the table. Which again: it can’t be off the table. That’s a very good way to ensure silence around the subject, isn’t it? Saying you can’t speak about it in fiction is adjacent to saying you can’t speak about it for real, which is already a problem that doesn’t need worsening by made-up rules of fiction.

So, take that subject, and filter it through the lens of Game of Thrones and then Mad Max.

Both use sexual assault in the storyworlds.

In Mad Max, you can’t accept women as “things” or livestock without then making the leap to say, mmmyeah, it’s probably not by choice. Okay? They didn’t sign up for it. That’s frankly the whole point of the movie, isn’t it? (Again, see the art above quoting the movie: WE ARE NOT THINGS.) If you leave Fury Road and look back upon the series, you see a few powerful women here and there (Aunty Entity, and, erm, that one lady with the crossbow?), and you also would get to see an on-screen rape scene in The Road Warrior — one viewed through spyglass at a distance, but it’s very clear what’s going on. The confirmation of women as object is shown when one of the women in Fury Road is cut open so that the child inside her can be seen, even though it may not be alive.

In GoT, rape is part of the fabric of life. It’s woven right in there. It’s almost background noise — I’m pretty sure if you turn on the show and zoom in, it’s like Where’s Waldo or trying to find Carmen Sandiego. There’s maybe always a rape happening on-screen somewhere, at some point? “Did you find the rape happening in every episode?” (It’d be like a really super-gross party game.) Characters talk about rape. They do it and exposit scenes while they do it. They accept it and expect it. Folks will say this is based on medieval history, though really, it’s based more on medieval myth, and of course, once you throw dragons and active godly magic into the mix you pretty much signal that you don’t have to base your fantasy (key word: fantasy) story on anything, really. (But “it’s based on history!” is always a good crutch for lazy storytelling, so whenever an editor or critic challenges you, don’t forget to say loud and say it proud.)

So, two very popular storyworlds.

Two portrayals of a world where women hold dubious power and are seen as “things.”

One of these is roundly criticized for it.

One of them is roundly celebrated for it.

Game of Thrones catches hell for its portrayal of women and this subject.

Mad Max is wreathed in a garland of bike chains and hubcabs for it.

What, then, is the difference?

Let’s try to suss it out.

In Game of Thrones:

– rapes often happen on-screen-ish

– they happen semi-often

– they happen to POV characters (Dany, Cersei, and now, Sansa Stark — given that there are six total assumed major female POV characters in the series, that means 50% of them have undergone active sexual assault on-screen)

– twice the rapist is a character we like (Drogo, Jamie)

– often used to motivate characters or sub in as character development

– seemingly meant to shock, often male-gazey

– history of it in the show

In Mad Max: Fury Road:

– the assault is implicit, not explicit, happens way off-screen

– not a focal point, per se, of character development

– though does provide seeds in the bed for character development — meaning, the event is hidden so that we don’t see it, but what grows up out of the dirt still suggests that it happened

– not much history of it — but again, Road Warrior has an explicit instance?

– we are never on the side of the rapist

– not male gazey because not on-screen and because of female POV (Furiosa)

I don’t know that this tells us enough yet, so let’s unpack it some more.

Frequency is an issue, for one: in GoT, we see rape and sexual assault again and again. In four seasons, we have three (ugh this sounds horrible to even put it this way) “major” rape events used as plot devices and character motivational tools (and that sounds even more horrible and icky). In Mad Max, we never actually see it at all. In Got, it happens often enough that you begin to wonder if there is a well-worn, oft-punctured notecard for the GoT storyboard that has written upon it: I DUNNO, PROBABLY RAPE?

Which also suggests that another issue is point-of-view. Where do you put the camera? Where do you place the narrative? Fury Road begins well after any actual assaults have occurred (with the exception of the “cutting out a baby” thing, which is more a byproduct of sexual assault rather than an explicit sexual assault). And none of it is on-screen. The story happens after. In Game of Thrones, the rapes are — man, this will never not sound gross — “ongoing.” It’s an ever-unfolding rape carnival, a parade of sexual assaults. (Here, by the way, someone will surely say something about why are we so concerned about the rape but, say, not concerned about murder or Greyjoy’s “dick removal scenario.” To which I would respond, frequency again becomes an issue: if every season contained one major dick removal scenario, you’d probably start to say, “Hey, Game of Thrones writers, maybe cool it on the cock-chopping. It’s feeling like you have a thing against dicks. Do you hate dicks? Why do you hate dicks so bad?” And here we could ask the same about women. Do you hate women? Why do you hate women so bad? Do you have a thing against them?

Of course, they don’t hate women. That’s absurd and we can’t really assume to be true — both Mad Max and GoT posit a world that hates women, though, so again, what’s the difference? GoT gives us the pain and suffering of women as part of a larger pattern meant to motivate characters. In some cases, male characters — in the assault on Sansa Stark, I have been repeatedly told that it “explains” what Theon Greyjoy does. I have no idea what that is, but I can guess that it’s something against Ramsay Bolton, and there I’d like to suggest that Theon (the subject of the earlier “dick removal scenario”) probably needs no more motivation to do ill against the Boltons given the aforementioned fact of his man-wang being turned into dick salad. Nor does Sansa require “motivation” to hate the family who literally murdered members of her family. We don’t actually need more, there. We do not require further “character motivation,” and if rape is the only way you can motivate your characters, you may want to go back to Writer’s School because I think you skipped a few crucial 101 classes.

What it then comes down to is a question of agency. (Here: a post on agency and women characters and how “strong female characters” are really nothing without agency and the ability to push on the plot more than it pushes on them.) Where you place the narrative camera and how you choose to affect the characters leads to the question of — what does assault do for the character’s power and choice in the story? Placing the events off-screen and before the film begins, Fury Road buries it well enough to explain why the characters are doing what they’re doing. The arc of those characters — the women — in Mad Max is one of going from zero to one. From a loss of power to a gain of power. The story is about the reclamation of agency — it’s them saying with great and violent effort: we are not things.

But in Game of Thrones, the opposite occurs. We witness powerful women undercut by assault. It removes their agency. (That is, quite explicitly, what sexual assault does.) They are robbed of power to motivate them, to make men feel bad, to make the audience feel sympathetic. But they go from one to zero. They go from something to nothing — from agent and actor upon the plot to victim of the plot. You might say that Dany is motivated to become the queen by the act, but first, that’s gross, and second, it’s also not true. She’s motivated only to become a wife and a lover at that point. Cersei is changed by the act — it would seem to begin her descent. And Sansa is just at a moment when we start to believe she has agency and power. She’s tougher. Harder. She’s taking on a whiff of Littlefinger’s machinations. The show wisely made it seem like reclaiming Winterfell was at least in part her choice. Her hair is dyed black. She appears a grim, death-like specter of vengeance. And she even says the right things: she indicates her lack of fear, she impresses her power on others. It’s a turning point for a character who for so long has basically been a whipping girl. She’s been a can kicked brutally down the road. And finally, finally you think — ahh. Here it is. Here she is claiming her power. Finding her agency. Here she will at last become, like Arya, a mighty force for change and no woman and no man will ever again dominate her and —

Oh. Oh.

She gets the black dye removed from her hair and it’s like Samson with his locks cut. Because along comes Ramsay Bolton — who is so eeeeevil I’m surprised he doesn’t have a sinister mustache to twist and a puppy to eat — to take that all that away as he gleefully assaults her. All as we focus on the poor weepy face of dickless Theon Greyjoy, who by the way is a child-murderer so wait why do we care about Theon Greyjoy again?

It’s not that GoT is poorly-written. That’s actually the shame — it’s often so well done. The show is really one of the best television shows around right now. It’s part of the Renaissance of hella good storytelling going on the tube at present. If it was a garbage-fire of a show, we wouldn’t even care. We wouldn’t expect better. But me? I’d like to expect better. Because its creepy fascination with hurting and marginalizing its women characters is increasingly gross and lazy.

Listen —

This isn’t about being shocked.

This isn’t about being offended.

It’s about something larger and lazier and altogether nastier.

It’s really about rape culture. About how this seeps in like a septic infection. About how it’s illustrated and handled with little aplomb, how it’s a default, how it forms an overall pattern.

Rape and sexual assault are fraught topics. To say you can never use them in fiction is, as noted, a terrible thing. We must be allowed to talk about bad things. We must be allowed to explore them from nose to tail to see what it means. Fiction is best when it doesn’t turn away from pain and suffering. It must embrace trauma. But that also means treating it and the characters who suffer it with respect. Make it an organic part of the story, not a “plot device.” A plot device is crass, cheap, lazy. Sexual assault is not a lever you pull to make people feel bad. It’s a trope because it keeps showing up — that’s not a good thing. Women are constantly fridged in these stories to make male characters feel something — to make the audience feel something. The problem isn’t in individual instances, you see? It’s in the pattern. It’s in how this keeps showing up again and again, a lazy crutch, a manipulative button the writers mash with greasy mitts, a cheap trick to rob agency and push plot. Meanwhile, you have actual rape victims in the audience who are like, “Hey, thanks for turning my trauma into cheap-ass plot fodder.”

In fact, let’s dissect that a little bit — RAINN suggests that 1 in 6 women have been the subject of some kind of sexual assault. A TIME study noted that, on campus, that number is 1 in 5 women. These are consequential numbers. Huge, scary, terrible. Now, realize that Game of Thrones gets some of the highest ratings on cable television — roughly seven million people watching. And in 2013 it was roughly 42% women who made up that audience. If you go low enough to accept the 1 in 5 number, you accept that roughly 588,000 sexual assault victims are watching the show. Even if you think that number is inflated — even if you assume it’s not 20% of all women but only 5% — that number still becomes 147,000. It’s a not insignificant number. It’s a marrow-curdling number. And it’s a number where each person affected has others who have been affected in turn — family, friends, other loved ones. Trauma is not a stone thrown against hard ground. It’s a stone thrown into water. It has ripples.

Ask yourself again: Game of Thrones versus Mad Max.

Would you rather see a world where the women declare in a barbaric yawp: WE ARE NOT THINGS?

Or do you want to be subjected to one where again and again it’s proven: WE ARE ONLY THINGS…?

Do we really not see the difference?

Do you not see why one would be celebrated while the other is excoriated?

Now, please go and read:

Sansa, Ros and Trying to Keep Faith — by Leigh Bardugo.

Then — Matt Wallace writes Try Harder, Do Better.

Comments closed.